Stonehenge wasn’t built overnight. In fact, it took 1,500 years for the site as we know it today to take shape. What began as a simple earthen henge in 3,000 B.C. evolved over time as the site grew and expanded into the Stonehenge we see before us today. But before we explore this topic further, you can learn more about the site’s fascinating history and visit it yourself with our Stonehenge Tours.

Stonehenge’s construction spanned several distinct phases, each lasting hundreds of years. During this period, the social, religious, and ethnic composition of its ancient Neolithic builders evolved, as did the Stonehenge site.

Stonehenge would become a mirror reflecting the evolution of ancient Neolithic peoples at the time. We have an article on why Stonehenge was built and by whom. In the meantime, let’s take a look at how Stonehenge was built.

How long did it take to build Stonehenge?

Construction on Stonehenge lasted approximately 1,500 years and spanned several distinct phases between 3,000 B.C and 1,500 B.C. The site at Stonehenge grew and developed over a very long period of time and was not completed all at once by its builders.

Phases of Construction

The First Phase (3,000 B.C.)

Construction on Stonehenge began around 5,000 years ago in 3,000 B.C. It was during this time that the foundations of the site, which would later become Stonehenge, were first laid.

Around this time, the ‘Heel Stone’ was erected at the entrance to the henge, marking the place on the horizon where the sunrise of the Summer Solstice appears.

Four ‘Station Stones’ (only 2 survive today) were also very likely placed during this period, although they may have arrived equally during Phase 2. These stones are set just inside the bank and, like the Heel Stone, align approximately to the Summer and Winter solstices.

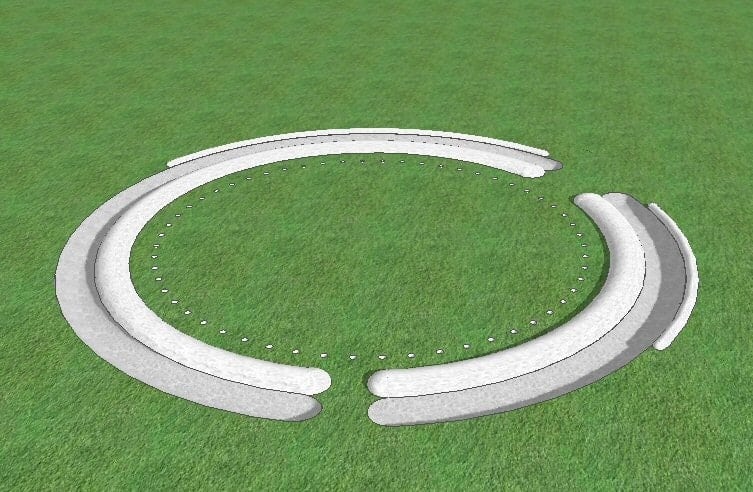

The first and oldest part of Stonehenge is a large earthwork, or ‘henge’, consisting of an earthen ditch (and accompanying bank) and 56 distinct ‘Aubrey holes’ dotted around the site’s perimeter. But what exactly are the Aubrey Holes?

The Aubrey Holes

In 1666, John Aubrey – an English antiquarian and writer – visited Stonehenge and observed a series of holes dug around the circumference of the henge.

The ‘Aubrey Holes’, as they came to be known, are a ring of 56 round pits dug into the chalk with an average depth of 1.06m (3.4ft).

Cremated human bones were found in many of the Aubrey Holes – but why?

Excavations have revealed cremated human bones (mostly men, with some women and children) in and around the holes. New research indicates these bones may have – mysteriously – come from people who lived more than 200 kilometres (120 miles) away from Stonehenge.

Crude picks made of deer antlers that were used to dig the ditch were also found in the holes, as well as the bones of cattle and deer.

The exact purpose of the holes remains a mystery, although the likelihood is that they were originally used to support wooden posts (or smaller bluestones) before later being used to bury cremated remains.

The Second Phase (2,900 – 2,600 B.C.)

Historians and archaeologists are unsure what—if anything—happened during this stage of construction. It wasn’t until the stones themselves began to arrive during Phase 3 that we started to see any signs of activity on the site.

As always, there are theories. One theory is that the Aubrey Holes (remember those?) are partially filled, and wooden poles appear during this time at the henge’s centre and near the northeastern entrance.

Wooden poles? Why?

The cluster of poles at the northeastern entrance may have served as markers for astronomical events, or it is possible that they were used to create a palisade fence that acted as an entrance to Stonehenge, which may have guided people through narrow paths to the ceremonial centre.

The Third Phase (2,600 – 1,500 B.C.)

The longest and most dramatic period contained the most changes, and it was during this time that Stonehenge, as we know it today, began to take shape.

The Bluestones Arrive (2,600 – 2,500 B.C.)

With the exception of evidence of human burials, Stonehenge remained largely untouched from its initial stages of construction for around 500 years. Then suddenly, around 2,500 B.C., the smaller ‘bluestones’ started to arrive.

Around 82 bluestones arrived from the Preseli Hills in Pembrokeshire, Wales – around 140 miles (225km) away.

How do all of these giant stones, some weighing up to 4 tons, end up at Stonehenge?

We aren’t sure. What makes this event truly mind-boggling is the fact that the people alive during this time were still using stone tools.

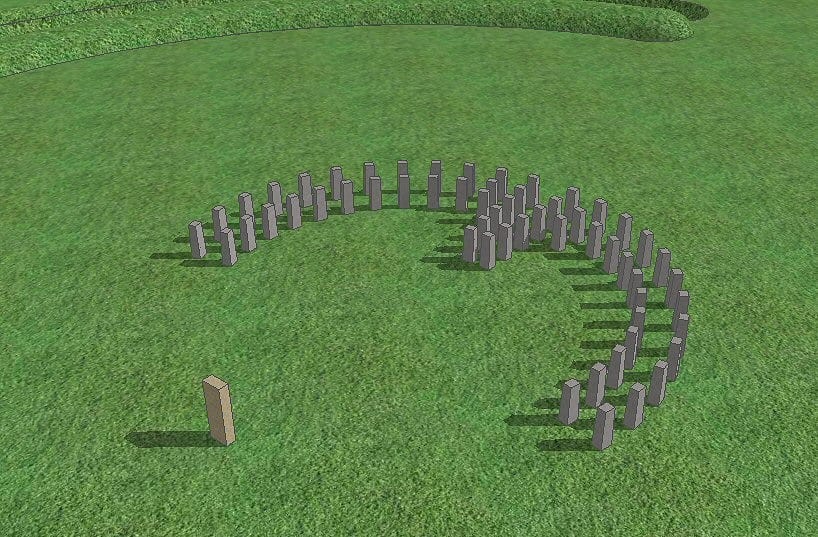

Archaeologists believe that the bluestones were transported by natural waterways and dragged over land. These ‘bluestones’ were then set up in two concentric half-circles.

The Sarsen Stones Arrive (2,000 B.C.)

At some point, a 100-foot diameter of 30 massive sarsen stones (weighing up to 50 tons) appears on-site and is arranged into the famous ‘Outer Circle’.

Horizontal lintels were then placed on top of the enormous Sarsen Stones, while a horseshoe-shaped setting of 5 ‘trilithons’ was constructed in what would become known as the ‘Inner Circle’.

What are the Sarsen Stones?

Sarsen itself is a type of hard sandstone only found in certain locations around England. The gigantic Sarsen Stones found at Stonehenge are originally from a site 20 miles (32km) north of Stonehenge on the Marlborough Downs in North Wiltshire.

Due to the immense weight of the stones, transportation by water would have been impossible; therefore, they could only have been moved using sledges, ropes, and a considerable amount of manpower.

Bluestone Rearrangement (1,500 B.C.)

Around this time, the bluestones were re-erected into the familiar formations that we see today: an oval perimeter around the inside of the outer Sarsen stone circle and a horseshoe shape within the trilithons at the centre.

A day trip to Stonehenge is the perfect way to explore this ancient and mysterious Neolithic site, so take a look at our unforgettable Stonehenge Tours.